In discussing the interactions between people and their environment in the African continent, particularly with reference to water, it is easy to essentialise one singular narrative of the situation at hand. It is through such tendencies that we derive homogenising frameworks, such as that of a "human ecology", defined by professors at the University of California, Davis as the biological basis for human behaviour. We have learnt that how this assumes that human behaviour is homogeneous, when it is in fact grossly disparate between individuals, (presumably) on the basis of their multiple intersecting identities. In social and cultural geography, we give much attention to intersectionality, examining how each of these multiple identities we hold – perhaps we're African, and/or female, and/or gay, and/or poor – holds different levels of social or cultural power, which facilitate or hinder certain choices, and even interact with each other to create different outcomes.

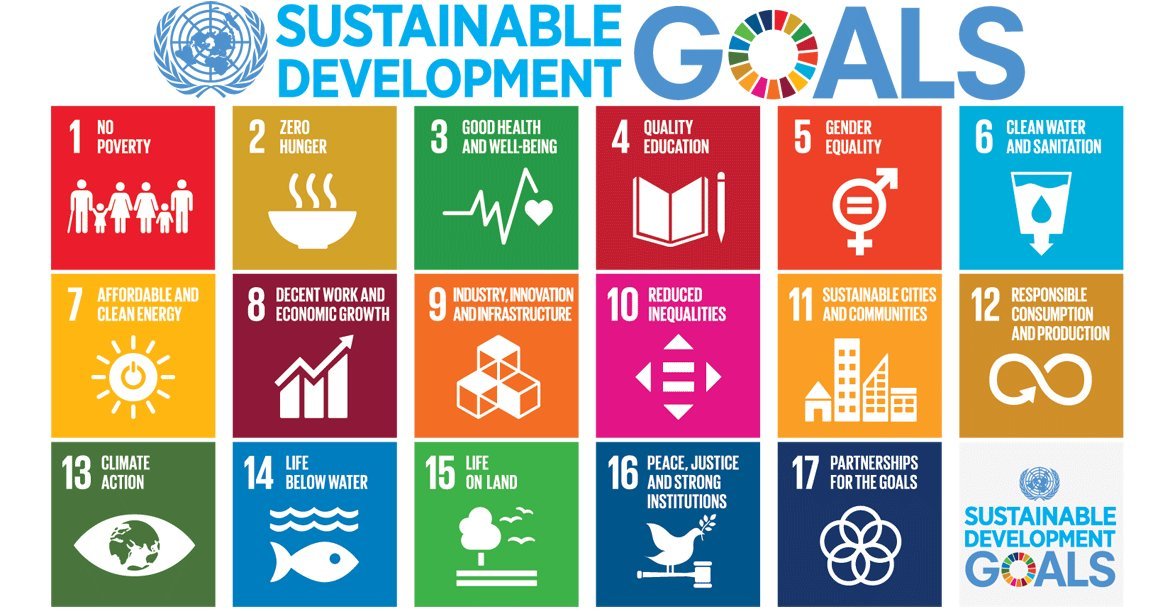

It is through this that gender enters the picture. Access to water is not a singular uniform process. Globally, women are often culturally and institutionally disempowered — we see this from the United Nations Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), both of which specifically note gender equality as an unachieved goal hindering the progress of humanity (see Figures 1 & 2). Furthermore, the specific structures and cultural norms which dictate what women can and cannot do almost always implicate water, given its role as a primary commodity or constituent in almost all human activity.

|

| Figure 1: Millennium Development Goals for 2015 |

|

| Figure 2: Sustainable Development Goals for 2030 |

For instance, certain social norms surrounding women may not be congruent with certain forms of water extraction for agriculture, as suggested by Villholth (2013). She discusses the degree to which groundwater irrigation specifically suits the “roles and capabilities of women” in Sub-Saharan Africa; quoting firstly women’s historical exclusion from land inheritance and thus the capital required to invest in irrigation equipment, and secondly the pressure on women to spend their time fulfilling “traditional “women’s”” chores” such as fetching firewood and, rather ironically, bringing food and water to their husbands working in the fields. Thus, though groundwater offers a stable alternative to otherwise fluctuant, weather-dependent surface waters, and hence such immense potential to increase yield – we see how the historical exploitation of female labour and institutional barriers to female autonomy impede African agricultural development and food security.

It is precisely because of this that we must question narratives of Africa as necessarily "water-scarce". We have criticised ethnocentric definitions of "water scarcity", for failing to consider that the overall demand for water on the continent just may not be as high as in other regions. Could improving access to water in Africa, then, be merely a matter of increasing equitability? Women, whether in agriculture or in the household, find water, prepare water, use water; women are water. Perhaps gender is the answer to improving the relationship between Africa and its water.

Well-researched first blog-post and I like how you link the topic to the SDGs! Also, I really like your focus on challenging the dominant narratives regarding the topic. Maybe it would be nice to mention why you are personally interested in this topic and a short personal introduction before starting with discussing the literature? Looking forward to the other posts :)

ReplyDeleteThis opening post set well the scene of the themes that your blog intends to address. Do be sure to cite peer-reviewed literature (e.g. Villholth, 2013) and other online sources with hyperlinks to the article or webpage.

ReplyDelete