Linda McDowell, the pioneer of much of feminist geography, pointed out that it was "remarkable" how 'sexless' geographical analysis was. Her words might still ring true today; for perhaps practical reasons, there tends to be a lack of distinction between the experiences of men and women in academia, particularly where gender may not be viewed as very relevant. Yet, we know gender affects daily life; it seems imprudent to even suggest that it would not be a relevant influence at any point in time.

Is it likely then that only a subset of the world's experiences are described by and explained in the literature? The problem is not so much so that it is difficult to account for every intersectional axis – gender, socioeconomic status, race, sexuality – in every analysis, but which intersectional axes are represented and have power. As echoed by Robinson (2003), while theory is often representative of a "supposedly unmarked" and "unlocated realm", it is in fact "profoundly tagged by its production in the dominant Anglo-American 'heartland' of graduate schools, research funds and publication outlets". Importantly, social identities are reconstituted through its intersections with other important identities across space and time, and the relationship between different social categories are not simply additive.

This is why it would be gravely inadequate for the literature on Africa's water problem to be focused purely on the experiences of "the urban poor", or the "rural". In fact, the identities of socioeconomic status, or rural/urban status, overlap, enmesh, interact messily with other social identities, and are dynamic through space and time. Precisely because much of academia is so Anglocentric and from the global North (albeit the problematic term), the realities and lived experiences of individuals in the "global South" are neglected or inaccurately portrayed. The poor woman in squatter housing in Cameroon lives a much different life from the poor man in Cameroon, though the current literature may analyse the situation

To end, I will highlight some possible instances in which the current level of analysis or academic narrative may be insufficient, and in doing so highlight the gaps in the current literature on Africa and its water problem:

Private sector water provision

I have discussed briefly before how though the private sector aims to funnel water resources ideologically "fairly" via the free market. However, this assumes that all other factors are constant (ceteris paribus), when in reality that is hardly the case. The free market does not account for much of the inequities that come with socioeconomic status, gender, and other axes of differences across society.

Transboundary water resources

|

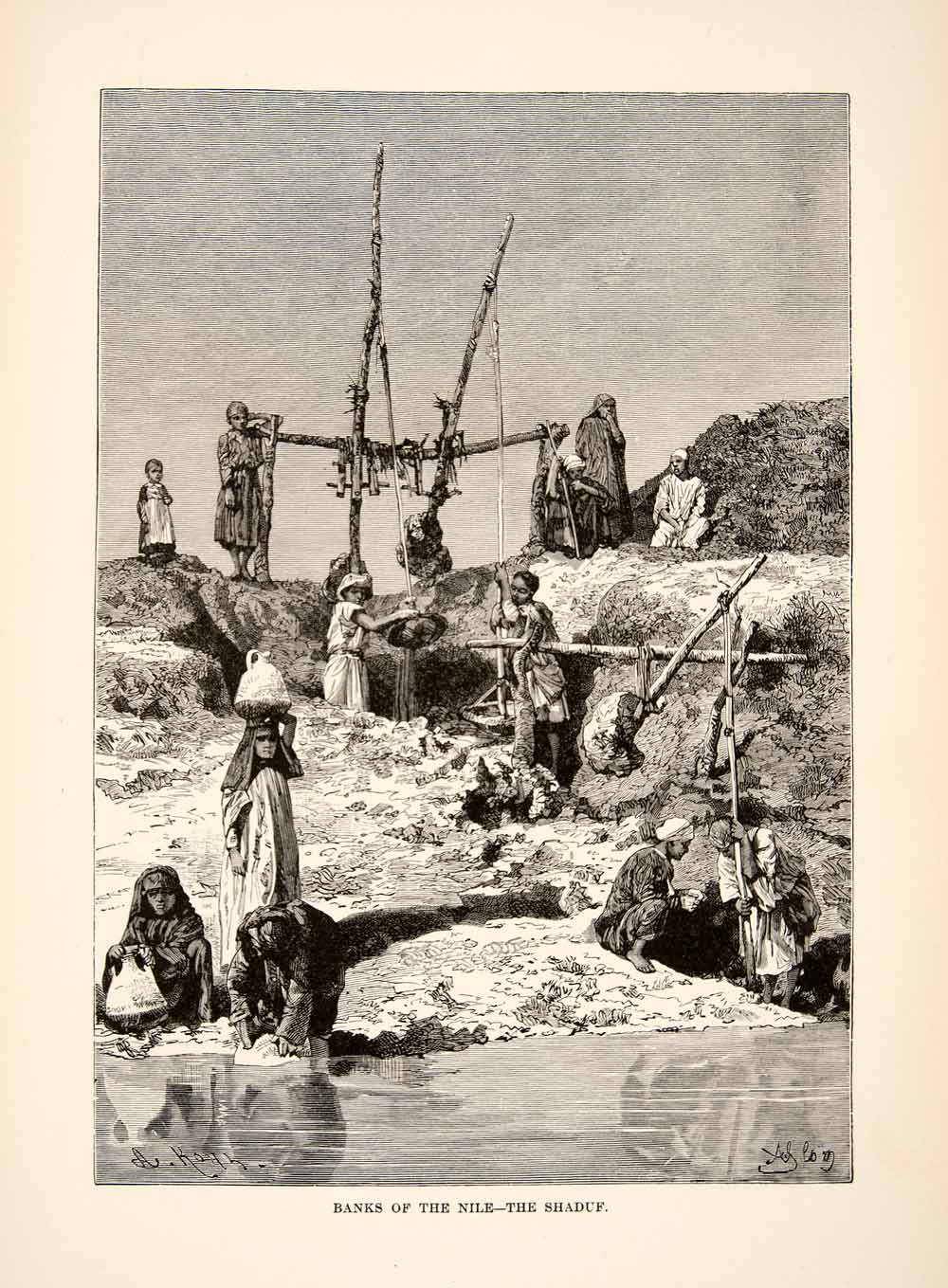

| The Shaduf, ancient Egyptian water collection device – observe the demographics in this work Source: https://cdn.shopify.com/s/files/1/1021/8371/products/XGJC1_020_743e57c2-f565-4e01-a9f3-ec1bb66c988a.jpg?v=1571713307 |

In that sense, could transboundary resources and historical infrastructure entrench women in the cycle of unpaid labour and water collection? A state that has been using water from the Nile for thousands of years have much justification for continuing to do so, but also has much justification for not changing much of the social circumstances surrounding water use. This has great implications for gender equality and women in Africa, and as states fight to keep control over transboundary water resources, they might in reality be fighting to keep their women struggling.

No comments:

Post a Comment